Over the years, SJ Vietnam hosted hundreds of volunteers from all over the world. We share with you a few stories about the time they spent with and, sometimes, the life-changing moment their volunteering led to!

When a workcamp ends up with a marriage: The Love story of Stefania and Sung Jae: two SJ Vietnam volunteers

!My name is Stefania, I come from Italy and I was a SJ Vietnam volunteer joining a workcamp roughly 2 years and half ago. It was in Vietnam, Hanoi, and it was the beginning of august. At that moment I was completing a stage in an Italian Ngo but for 2 weeks I took part in a SJ Vietnam workcamp focusing on takin’ care of the Fishers’ Village on the Red River.

Actually the project guidelines took immediately my attention and I really wanted to apply just to give an hand in it.

I applied with Tham, my super collegue, and together we could experience 2 unforgettable weeks together with French, Swiss, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Koreans…..with Pierre a coordinator from Belgium. For 2 weeks we spent every single minute together, discussing (too much about every single thing; democracy sometimes is an hard process…) staying with the children of the Fisher Village, cooking, projecting, doing our best and most of all knowing each others….!

I applied with Tham, my super collegue, and together we could experience 2 unforgettable weeks together with French, Swiss, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Koreans…..with Pierre a coordinator from Belgium. For 2 weeks we spent every single minute together, discussing (too much about every single thing; democracy sometimes is an hard process…) staying with the children of the Fisher Village, cooking, projecting, doing our best and most of all knowing each others….!

I will always remember it as a very unique chance to know other people, Countries I never focus my attention on, a chance to learn how to live together despite of our different attitudes. But I don’t want to speak about that…the purpose of this short letter is to tell about a very special meeting, that changed my life quite deeply (too much deeply?).

Who doesn’t experience a love affair during an hot summer in a tropical Country, working for the same thing you believe in? The point is what’s the difference between a love affair and a marriage? Me and Sung Jae, the first Korean human being in my life, just believed in our feelings, that’s it.

It’s long to explain how we falled in love; curiosity at first and mysterious attachment in the end. When I met him it was even hard to understand his English! Behavior, language, trying to imagine where he is coming from, it requires time! But that’s what the workcamp gave me; the time to speak with a person that comes from far away, nights and day to talk and learn about each others.

Needless to say, all of us, volunteers, didn’t sleep very much; people were really talkin’ and enjoing staying together, it’ was an amazing scenery to see. The experience was great only for the reason we worked all together. But the 2 weeks ended and after the tears people have to face the “crude reality”.

Was it all a dream or not? Do we really want to continue this mysterious process we started with ? We decided to go on and see.

Through SJ Vietnam I founded another chance to continue. I joint a middle term project in Korea reaching him only some months later; the purpose was to know his Country in order to really understand who he were (and who he is). Then I went there, I participate in another educational project through the NGO IWO in an alternative school called Gandhi School. It was the starting point for estabilish myself here.

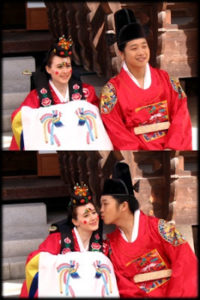

Now 2 years and 4 months are passed. I am still in Korea….and we married!! It was not always a dream as during the 2 weeks in Vietnam but we can really say we built our selves findin’ the way to stay together. To continue our love it was important to be practical; find a house, find a job, learn Korean! Actually I became Italian teacher here in Seoul and he worked full time in a trading company. Since 2 years we are living together; we were not so sure about our future (especially comin’ from 2 completely different Countries) but we simply tried our best to build something.

Now that we established here we WANT TO REBEGIN FROM 0; in Italy this time. Korea was really suitable but for an International Couple like us the way to find our place is not so easy, we need to try, to compare, to decide what’s better for us. Then now Sung Jae is in Italy and I am endin’ up with my job here. From the next month we will be there and again house, job, life in another country, this time for him. Now I can have a normal conversation in Korean and he’s’ studying Italian since 1 year, he is so far better than me.

I didn’t realized well when it happened but now (after long efforts…) we can communicate in our native languages. I think this is to biggest accomplishment to be close each others!!!

All this to say only one thing; don’t miss the chance to know other people, different people because maybe it will be the one that will change your life, in a small or big way!!!

A workcamp it’s first at all a chance. You never know what a new Country and a new friend will bring to YOU! Just share your dreams with someone and as we say in Italian “se sono rose fioriranno!” (if is true love, it will bloom!), love is action, desire to know more, love is takin’ decisions!

With love

Stefania Micheletti

Written by Stefania Micheletti([email protected])

See her pictures on her web site: www.cyworld.com/soratobupaul

Water filters on the Red river

A mighty river flowing from southwestern China, going all the way to northern Vietnam and emptying itself to the Gulf of Tonkin is the Red River. The reddish-brown heavily silt-laden water gives the river its name. The Red River is notorious for its violent floods with its seasonally wide volume fluctuations. And today we are paying it a visit, particularly, towards fisher village, a floating community along its banks in Hanoi.

To get there, we have to walk on Long Bien Bridge, designed and constructed by Alexandre Gustave Eiffel at the turn of the 20th century. It was opened to traffic in 1902. Of great strategic importance, it carried the only rail link between Hanoi and the main port of Hai Phong. During the war for independence, it was bombed repeatedly by American fighter planes F-105 Thunderchiefs and F-4 Phantoms. In order to halt the bombs, the bridge was repaired using American POWs.

Along the way, we saw people including very young children emerge from the hollow steel frames of the bridge. We tried figuring out how were they able to crawl past narrow passages along the frames that snake across the bridge. One missed foothold means plunging 40 feet down the cold waters below. The bridge is 1,682 meters long and is part of Hanoi streets. But due to age and wartime wounds, it is only used for train, pedestrians and bicycles, no vehicle is permitted.

At the bottom were corn plantations, and footpaths that lead us to one arm of the Red River towards a community of floating houses. These residents are too poor to pay the rent for a piece of land where to build their little shacks. The floating houses need to be occasionally moved in preparation to rising waters, lest they sink at the bottom. The friendly floating residents beckoned us for tea, which we willingly oblige.

The residents’ source of water is the Red River which needs filtration before being boiled for drinking and cooking. So today we are making a UNICEF-designed water filter to be donated to the floating residents. Right across the river is an island formed by alluvial deposits used for growing vegetables and spices. The yearly floods brought in the nutrients, so the farmers do not need fertilizers. But more than half of the farmlands will be submerged when the rain comes.

We hopped on the island going towards the other side facing another arm of the Red River where it has a football field. Interestingly in cold Hanoi, nude local footballers play here in the afternoons unmindful of the dark history surrounding the area. On the right side of the floating houses were concrete columns rising thirty feet in the air which line the river bank all the way to Long Bien Bridge. These sturdy pillars are mute witnesses to the atrocities of the past during the French colonization of the country where hundreds of Vietnamese POWs were said to be tied to the posts and shot here.

Back at one floating house, people gather to knit “revolutionary” acrylic sponges to be used as soap-less dish washers. While they were engrossed with knitting, I noticed a soft but high pitched melodious humming coming from the next room. It was a mother swinging a hammock and singing a lullaby to her little child.

Enduring the rain and cold wind outside, the others clean sand while we were all warm and comfy making the water filter demonstration inside. For this, we need two (2) pails, one big, the other small. The small pail is to be placed facing the big one’s bottom. Clean sand, carbon filter and hoses will be put in place later. I was asked to remove the red pail’s white handle. I obliged, and I was successful in jerking the handle loose, but broke the pail. (There was muted laughter.) Then I carved a hole on the bottom of another red pail using a heated red knife. I did as told, but made a crack emanating from the hole. I continued with the task, until the red handle separated from the blade. (Laughter erupted!) Too clumsy for the task, I left to clean sand instead….

(from the journal of Jun, Philippines Leader during NVDA meeting in Hanoi, january 2008, [email protected])

When asked by Pierre De Hanscutter to write this mini article on my time in Hanoi with SJ Vietnam, one year later, I hesitated for one pure reason. No matter how I try, I cannot do justice to bring alive the emotions I felt and the sights that I saw whilst I was in Hanoi for a brief period of two weeks. Therefore, my objective in this article is to compare and to contrast my feelings now with my experience of then, to draw learning experiences and to encourage others to take part in such schemes, despite the ups and the downs during the fortnight as an international volunteer.

Two weeks. When said like that, it sounds minute, too short a time to really understand a country, or specifically in this case the fisher village people. The fisher village project was the base of our work: A dozen or more children ranging from infant to teenage years who came to the school everyday for a meal and for two hours of English lessons. Our days consisted of various chores: going to the market, preparing and cooking food for the children, teaching English (shouting and disciplining as well as playing are a part of this), cleaning two houses from top to bottom, cleaning sand for the water filters, taking the children out to the swimming pool and amidst all of this chaos, getting to know our team of volunteers.

It wasn’t easy. But we had a fantastic group of international volunteers and a strong leader, an eclectic mix ranging from Japan, Korea, Italy, France, Britain and Australia. A truly motivated group of young twenty some-things, happy to work, to sweat profusely whilst chopping up tofu, to work in conditions that weren’t always ideal. To name but a few mishaps, it all began with the water or rather a lack of it In the school for most of the time there was no running water, and when cooking for 15 kids plus all the volunteers, it gets less fun. But that was exactly the point of international volunteering, the hard work brought us closer together as a team, we laughed at all the crisis’ that knocked on our door everyday. Then there was the police who kept asking us for our passports, suspicious of our presence in the school. At two am, being asked to show your passport whilst in your pyjamas is no joke!

But the most challenging aspect of the work camp was undoubtedly the kids. Raucous, full of life, smiling, tough, to name but a few of the adjectives that meagrely describe their little personalities. Street kids would be the wrong term, but the definition is similar. Children who live on crowded floating wooden shacks along the Red river, who pick up rubbish to earn their living, children who see drug abuse and lives tainted by misery of no potable water, unemployed parents and the inability to break into the Vietnamese national schooling programme due to high levels of illiteracy or years of missed education. I won’t deny my first impression of these kids: Dear god! What have I let myself in for… I questioned myself everyday, I thought it’s impossible to teach them, to discipline them, to make them quiet. I got immensely frustrated, and my heart sank each time a new teacher would flee in fear after a trial period with them.

And I suppose that’s where I’ve changed and where I began to adapt my way of thinking as the two weeks drew to a close. These kids are like any other kids. What makes them different is their circumstances, I had to stop looking at the situation with my western tinted glasses and understand where they were they coming from. More than anything, these kids need affection, compassion and a long lasting teacher which the international volunteers could not provide them with. When you are in a country for two weeks you are not going to change the world of these kids and you are definitely not going to improve their English skills if you are teaching them the alphabet for the fifth time! (On a practical level, I would say that for the future success of the camp, a folder detailing everyday actions would be immensely useful to every group, and would certainly improve teaching standards of the volunteers.)

No, you are there to share your compassion, affection and your culture. You are there to be open minded, to break ice barriers and to forge bonds between you and everyone else. You are not there to judge nor to mock another way of living. A perfect example of this culture clash was the permission of the Solidarité Jeunesses Vietnam leader to let two boys sleep in the school. The two boys had been sleeping under the bridge because one of their fathers had forced them to sell hard drugs, but the boys refused, with dramatic consequences. The father left the boat and the boys were homeless. The outcry from the Western volunteers was no! In our heads we saw social assistants, foster homes, typically westernised structures, but none of that exists for these kids. It was either the bridge or the school, hallelujah for the latter.

So take a step back. This is what I’d say to the next volunteers: Appreciate another culture/other cultures, another way of thinking. You don’t always have to like it, just accept it, if you go with an open mind and don’t set high expectations, you won’t be disappointed. And you’ll make some friends along the way too. It’s an intense period of highs and lows but it’s worth it. How lucky are we to be able to live and breathe another culture half a way across the world! The proof of that: give me a ticket and I’ll be back in a second in the country of “moto, moto” cleaning the school and laughing with the children and the volunteers.

Elizabeth Lee,French volunteer in the FV camp, August 2006, Hanoi.

After her workcamp, Lee decided to join the french organization “un ETAI pour le Vietnam” based in Tolouse where she lives and continues her involment.

It is 2:00pm and Hanoi’s heat is as stifling and claustrophobic as a damp wool sweater that is three sizes too small. The bodies of Korean, Canadian, and American volunteers glimmer with sweat- filthy from traffic exhaust and mosquito repellant. The women no longer bother to wipe the perspiration that streams down their temples, backs, and legs. Only Thuy, the group leader – who is from Hanoi– is as sweat-free as the scores of women who glide down the road on mopeds in long-sleeved shirts, pants, facemasks, and hats.

The group marches through the pediatric hospital’s security gate, and troops up six flights of stairs. They visit a different floor each afternoon, clomping past parents who carry or lead their sick children up and down the steps. The elevator, as the volunteers are told, is reserved for the doctors.

The group marches through the pediatric hospital’s security gate, and troops up six flights of stairs. They visit a different floor each afternoon, clomping past parents who carry or lead their sick children up and down the steps. The elevator, as the volunteers are told, is reserved for the doctors.

Each floor has a community room, which is an open space lined with some blue plastic chairs, a few tables, rattan mats on the linoleum floor, and faded paintings on the wall that vaguely resemble Richard Scarry characters. There is no air conditioning and no electric fans – only respite from the penetrating glare of the sun. As the volunteers unload toys, games, and balloons from plastic bags, mothers poke their heads out from the rooms down the hall and file in with babies on their hips or bashful older children in tow.

One volunteer mans the pump, shooting air into long skinny balloons and passing them through the small assembly line of artists who twist them into various shapes: flowers, dogs, and bunnies. The novice volunteers’ balloon creations are more abstract. It is hard to keep up with the demand: mothers have poured into the room; each determined to get one or more balloons. Some of the children squeal with delight; others, defeated by the heat and illness, appear nonplussed. By now, the volunteers know that they are really creating the balloons for the parents, a patch of bright color in an otherwise dismal day.

Several of the volunteers alight on the rattan mat, spreading toys and coloring books across the floor. Soon they are joined by babies plunked down by their mothers, and by children bold enough to sidle over alone.

Two Korean volunteers unpack small squares of brightly colored Origami paper and begin folding. A bend, a crease, a tuck, and a flower emerge. They reach for more paper, and a couple of little girls float over, wordlessly, to join them, watching and mimicking each step of the process. The volunteers hand the paper flowers to children who meander past, and stockpile others to be distributed to the rooms.

A cadre of volunteers gathers small cartons of milk and handfuls of balloons and origami flora, and head down the hall to make special deliveries. Like the common area, the patients’ rooms are not air-conditioned. Children sit or lie on beds covered by rattan mats – there are no white sheets, no fluffy pillows, and no televisions positioned on the walls. Mothers attempt to combat the heat by fluttering fans at beleaguered faces. The rooms accommodate several children of all ages and their mothers. In one room, an infant wails from a bed just beside that of a ten-year-old boy who sits bent over a Manga comic book.

Unlike the cancer ward on another floor, it is not always glaringly evident what afflictions the children on this floor are battling. In halting English, Vietnamese, or gestures, some mothes try to explain. One woman clutches an infant with yellow skin, and explains in Vietnamese that he has jaundice. Another mother points to her young boy’s back, indicating a problem with his spine. Other children’s illnesses go unnamed.

The volunteers hand one small carton of milk to the infants’ mothers, and to the older children, along with a balloon or Origami flower. It is a token gesture, a fleeting moment. Some mothers, embattled by the circumstances, accept the offering with mild wonderment at this brigade of multi-national women who have descended upon the hospital. Others brighten and chatter animatedly.

One volunteer in particular has everyone’s attention. Patricia lives in Philadelphia but is originally from Ghana. Judging by the reactions she gets, she is apparently the first African woman many people in Hanoi have seen. Some people stare, some point, others giggle. A few people have been so bold as to reach out to touch her braided hair or dark skin, and even stroke her butt. The hospital is no different: she turns heads wherever she goes.

Here in the hospital, the shock and curiosity morph into delight. Patricia is studying to be a pediatric nurse and where other volunteers hang back, unsure and reticent; she forges ahead, lifting babies from mothers’ arms, striding up to retiring boys, and cooing at toddlers until they wiggle with delight. Even when a baby in cloth diapers urinates on her lap, she remains undaunted; she goes to wash up and returns within minutes.

After the rounds, the volunteers’ head back to the common area. Patricia and Kimi, a Canadian national, join You Kyung and Jin, two volunteers from Seoul, Korea. They stand in a line on the edge of the mat and sing a nursery school song that the Korean volunteers have just taught them the night before, complete with exaggerated facial expressions and gestures. The singing turns children’s heads and nurses gather, smiling, at the fringes of the room to watch the show.

It is also a bright moment for the nurses, who like all nurses, work long hours. But the nurses’ wages are abysmally low here, and so meager for doctors that they often pick up additional shifts. The doctors are well qualified but must contend with limited supplies and cramped conditions. So although a surgery might be highly successful, the recovery period is most dangerous, as sterilization problems and overcrowding can mean rapid contagion.

It is also a bright moment for the nurses, who like all nurses, work long hours. But the nurses’ wages are abysmally low here, and so meager for doctors that they often pick up additional shifts. The doctors are well qualified but must contend with limited supplies and cramped conditions. So although a surgery might be highly successful, the recovery period is most dangerous, as sterilization problems and overcrowding can mean rapid contagion.

After three hours in the hospital, it is time to quit for the day. Volunteers from this work camp will come each day for two weeks, then be replaced by the next batch of volunteers who come from all over the world. Each can only hope to provide a glimmer of happiness.

©Jennifer Anthony

More information about Ms. Anthony can be found at her website: www.jenniferanthony.net